Staff Tutor and Associate Lecturer, Jennie Owen, travelled to Prague to present at a conference on the theme of Global Horror. The conference was run by Progressive Connexions, an organisation that supports sustainable global interdisciplinary research, and promotes collegiate exchange of ideas, experiences, and points of view.

This emphasis on curiosity, open-mindedness, and collaboration is also at the heart of our Contemporary Cultures of Writing conference on 20th April, which Jennie is organising. You can book here for tickets to this London-based one-day conference: Writing place: what haunts the landscape of modern Britain?

Today, Jennie offers us a glimpse into the kinds of urban legends that inspired her paper, ‘Cursed Poetry: An Exploration of Ekphrastic Poetry Inspired by Cursed Art’.

At the Darkness at the Edges conference, delegates spoke on varied topics, from the gothic and dystopic in Indigenous fictions to fairy tale motives in German post-war literature.

I’ve long had an interest in horror, as well as the gothic and dystopian. My particular fascination with cursed paintings began as a distraction from the more challenging sociological aspects of my PhD research into traumascapes in the northwest of England.

The notion of the modern-day curse is often propagated through social media, and I was fascinated by how these urban legends become fragmented as they are retold online on websites and community forums.

But the idea of the curse is not a new one. We can trace its path through ancient history: it’s discussed in the Bible, linked inextricably to our perceptions of ancient Egypt, and a common inciting incident in the fairy-tale narrative. In common folklore, a portrait that falls to the ground may foretell the death of a loved one; whilst anyone who was a fan of the cartoon Scooby Doo will be aware of the risk of the eyes in a portrait following you around the room.

One of the most famous cursed paintings in the UK is The Crying Boy by Giovanni Bragolin (1911-1981) – an image of a smudge-faced toddler looking sadly out at the viewer, tears running down his face.

In 1985, the Sun issued a warning that around 50 houses in Yorkshire had burned to the ground, leaving only this painting intact. This created a mild panic, reflected in a series of subsequent articles with headlines such as ‘Crying Flame’ and ‘Crying boy curse strikes again’. Such was the panic that on Halloween the Sun burned dozens of these paintings, which had been sent to their offices, and quoted a fire officer who stated: ‘I think there will be many people who can breathe a little easier now’.

There is a rich vein of allegedly cursed artworks. Man Proposes, God Disposes by Sir Edwin Landseer (1802-1873), which hangs in Royal Holloway University, has to be covered with a Union Jack during exam season to allay students’ fears that they might fail or lose their minds if they spend too long staring at the painting. Indeed, its subject matter is rather gruesome: two polar bears fighting over the remains of the 1845 Franklin expedition. This infamous expedition was designed to locate the northwest passage in the Artic, and resulted in the loss of two ships and all men aboard (and rumours of cannibalism).

There are dozens of mysterious contemporary pieces too: having once seen it, for instance, who can forget the Momo Whatsapp curse, which featured a distorted wide-eyed sculpture by Japanese artist Keisuke Aiso?

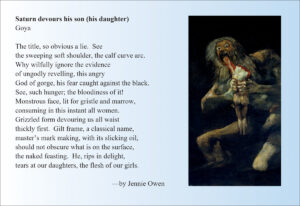

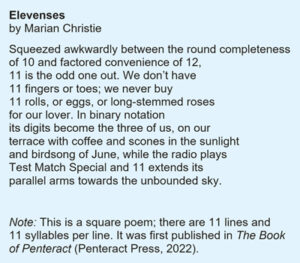

Using close examination of supposedly cursed art in the public domain, I used an ekphrastic methodology to create a series of poems.

The Poetry Foundation defines an ekphrastic poem as ‘a vivid description of a scene or, more commonly, a work of art. Through the imaginative act of narrating and reflecting on the “action” of a painting or sculpture, the poet may amplify and expand its meaning.’ It is hardly a new form of poetry – just think of Percy Bysshe Shelley’s ‘On the Medusa of Leonardo Da Vinci in the Florentine Gallery’ or ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’, by John Keats. But ekphrastic poetry does appear currently to be celebrating a kind of renaissance in popularity.

With international colleagues from a wide variety of disciplines, I shared my practice-based research by discussing my own creative process of using art as a means of inspiration for poetry. I explored how this approach has had an impact on both the form and content of my writing, as well as how the writing of these pieces both celebrates and challenges the concept of cursed art.

My presentation was received, I hope, without any undue residue of curses.

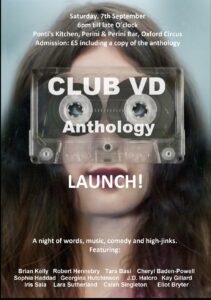

Jennie E. Owen’s cursed poems will be featuring in an anthology pamphlet published by Nine Pens Press later in 2023. Jennie has worked as an Associate Lecturer here at the OU for nearly 20 years. She is now also a Staff Tutor in Creative Writing, and lead Cluster Manager for A363, our level three undergraduate creative writing module. Jennie is working towards her PhD with Manchester Metropolitan University. She is a Forward– and Pushcart-prize nominated poet and writer of short stories, whose work has been widely published in anthologies, journals and magazines.