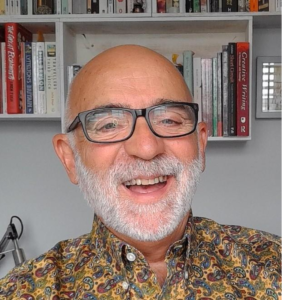

Dónall Mac Cathmhaoill, Open University Lecturer in Creative Writing, has been collaborating with University of València colleagues who share his interest in contemporary Irish theatre. Together, they have been exploring the relationship between performativity, truth, and documentary sources.

Here, Dónall offers us a glimpse into this relationship, and tells us how these shared research interests have informed his recently published article in Platform: Journal of Theatre and Performing Arts.

The University of València’s Rectorate (This image is in the public domain)

València in spring is generally a relaxing, pleasantly warm place to be. So I was very much looking forward to conducting a couple of seminars with the Departament de Filologia Anglesa during the month of Las Fallas – the Valencian festival to bid adiós to wintry days.

I came out expecting warm Levante breezes and two-hour terrace lunches with academic colleagues. Unfortunately, València has been experiencing some of the coldest, wettest weather ever for this time of year: high winds and incessant rain. (Being Irish, I felt right at home.)

The research trip evolved through my connection with Dra Maria Gaviña Costero, an English literature academic who specialises in the literature of the Irish conflict, particularly drama.

Given my own research into theatres of conflict, we found we had many interests in common. Having contributed some suggestions of writers the department might consider for their new drama module, I was invited last year to speak at their annual conference.

The idea then developed to deliver a research seminar and workshop with the university undergraduates in English, looking at performativity, truth, and documentary sources in Irish theatre.

The plan was to develop this collaboration to create a research paper on the work of Northern Irish playwright Stacey Gregg, who I had recommended for inclusion on the undergraduate drama module. Gregg agreed to take part in the session I would deliver.

Scorch by Stacey Gregg

The design of the research process was simple enough: the students would take part in a drama workshop where the contingent and subjective nature of dramatic truth would be explored. This involved creating dramatic narratives from ostensibly ‘true’ and ‘real’ material: documentary drama by another name.

The credibility of the narratives was predicated on their affective and aesthetic qualities: on the extent of identification between audience and performer, and on the presence of aesthetic signifiers of truthfulness, such as simplicity and directness of presentation, what Elizabeth Burns calls ‘authenticating conventions’ (1972, p.108).

Importantly, though, the narratives would be considered truthful through the rhetorical convention of having them presented by ‘real people’. This is a technique which has been used in northern Irish post-conflict drama, and which has been subject to academic scrutiny (Upton, 2010; Weigelhofer, 2015; De Ornellas & Mac Cathmhaoill, 2021).

Some, notably Carole-Anne Upton (2011), have called into question the assumptions upon which this work is built. The workshop and seminar explored how truth, and indeed identity, in documentary drama are contingent and subjective, performative and in flux.

The follow-up seminar, just completed, saw Gregg joining us online from Belfast for a discussion and Q&A. The undergraduates had by this stage read Gregg’s play Scorch, which is written from documentary sources. Gregg outlined the strategies she used as a creative writer to ensure truthfulness and fidelity to source in a work that is both documentary and fictional.

These methods – including in-depth case research, interviews, consultations with subject specialists, and presentation of work-in-progress – allow her to write plays that do not claim to be ‘the truth’ but that are unquestionably truthful.

The themes of these seminars will provide the material for upcoming research papers. They are also explored in my journal article in Platform: Journal of Theatre and Performing Arts, 15 (2): ‘Boundaries: respecting authenticating limits in the production of a play on trans marginality’.

Dónall Mac Cathmhaoill is a lecturer in Creative Writing at the OU. His PhD examines modes of authorship in theatre for social and political advocacy. His research interests range from authorship in theatre for social change to advocacy theatre in post-conflict societies. As a writer-director he has wide experience working with communities in Ireland, the UK and beyond. He was director of Irish theatre company Tinderbox, a producer and Head of Education at Soho Theatre, and has worked with major theatre companies including Bruised Sky, London; 7:84 Theatre Company, Scotland; Jagriti Theatre in Bengaluru, India; and Irish language company Aisling Ghéar.

Works cited

Burns, E. (1972) Theatricality: a study of convention in the theatre and in social life. London: Longman.

De Ornellas, K. and Mac Cathmhaoill, D. (2021) Addressing the legacy of inter-communal violence through drama: mainstream theatre and community action. In: Glencree Journal, 2021, 163-174.

Gregg, S. (2016) Scorch. London: Nick Hern.

Mac Cathmhaoill, D. (2021) Boundaries: respecting authenticating limits in the production of a play on trans marginality. Platform: Journal of Theatre and Performing Arts, 15 (2), 111-117.

Upton, C.A. (2010) Theatre of Witness: Teya Sepinuck in conversation with Carole-Anne Upton. Performing Ethos, 1 (1), 97-108.

Upton, C.A. (2011) Real people as actors – actors as real people. Studies in Theatre and Performance, 31 (2), 209-222.

Weigelhofer, M. (2015) The function of narrative in public space: witnessing performed storytelling in Northern Ireland. Journal of Arts and Communities, 6 (1), 29-44.

Narrative Imperialism and Writing Home: A conversation between Rebekah Lattin-Rawstrone, a new PhD student, and Sarah Butler, a recent graduate

Rebekah Lattin-Rawstrone has just embarked on a PhD in creative writing funded by the Open-Oxford-Cambridge Arts and Humanities Research Council Doctoral Training Partnership. We put her in touch with Sarah Butler, who was recently awarded her own PhD in creative writing, which was also funded by the AHRC – in her case via the Consortium for the Humanities and the Arts South-east England. Here, Rebekah and Sarah let us eavesdrop on their conversation about their writing and research.

Sarah Butler

Rebekah Lattin-Rawstrone

Rebekah: It’s a privilege to be given this chance to focus for three whole years on something that really fascinates me – narrative imperialism in the contemporary British novel. But that privilege brings responsibility with it.

Sarah: I’d love to hear more about the concept of narrative imperialism.

Rebekah: This gets right to heart of what I’m hoping to explore in both my critical writing and in the novel. I intend to unravel this concept from several angles: firstly, looking at the development of the novel during a time of imperialism and asking if that affected the narrative structures widely adopted in the form, particularly the three act teleological structure based around conflict and resolution; secondly, building on feminist criticism of narrative structures, thinking specifically of Ursula K. Le Guin’s wonderful essay ‘The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction’ in which she outlines the possibility of new story forms that don’t follow the spear, or the arrow model – the hero’s journey model – but the gathering, containing, holding model, arguing that the bag rather than the stick was the first human tool; thirdly, looking at the wide adoption in the creative writing industry, both academic and commercial, of the three act structure and the hero’s journey, especially under the influence of film theory, and asking whether, as the industry attempts to publish different stories it could also look for writing that tells these stories differently (put in another way, are we only interested in different stories when they fit into a certain story telling structure? Are we continuing to enforce a kind of narrative imperialism?).

Sarah: This is so interesting! I teach creative writing at Manchester Metropolitan University and have been reading critiques of the workshop model by writers coming from different literary/cultural traditions. I’ve been thinking about the assumptions I make about structure and form, and about how I support writers and writing from backgrounds different to my own.

I set off on my PhD thinking I was going to write about narrative and ageing and particularly about endings and death, but very early on in the process my supervisors asked me to ‘just write something’ reflective about my work. I ended up writing an essay about home across all of my published work, and realised that it is a huge and pressing theme for me.

Rebekah: I read your response with real delight because the concept of home has been a driver for my work too. I was born overseas and my father then became a diplomat so I spent a lot of time abroad as a child and it has had a huge impact on how I think about where and what I call home and how that might relate to a sense of belonging. You can see how all of these things then fed into an interest in world literature and a wider storytelling practice.

My first novel is actually called Home. It is about a corrupt care home, and I was trying to explore the fractures in the English extended family unit. Age, death and home – more common themes with you. My second novel is about a white English woman trying to forge a relationship with her Malawian half-sister. The desire to create a sense of family and home across national boundaries is central to this book.

I’ve begun by investigating possible alternative narrative structures and am having a lot fun looking at Islamic architecture and the mathematics of tessellation as a possible model for my novel’s structure. As the novel is partly set in Iraq, there is a real wealth of early literature to draw on. It makes for an interesting contrast with my protagonist, real-life adventurer Gertrude Bell who, as someone very keen to contribute to world events, did her best to fulfil the hero’s journey – albeit the heroine’s journey. I’m interested in her life outside of the public eye and how what often really fulfils us in life isn’t always our achievements. In that way, both the subject of the story and the telling should cohere as they attempt to express something different to the traditional three act structure. There will be other threads to the novel too, adding to that sense of pattern and structure through tessellation.

Sarah: I am a bit obsessed about applying structures from different disciplines/places onto writing, so I love the idea of taking ideas from architecture and maths and using those to find a structure for your novel. The way the form and the content are working together also sounds fascinating (and very satisfying!). It’s also really interesting to me because I have an idea for a new novel that I’m struggling to impose a traditional structure onto – I feel as though this conversation has given me permission to think that might not be such a bad thing!

When I started out on my PhD, I worried that ‘over’ analysing my own work would somehow damage my creative process. In fact, it’s been just the opposite. Spending time really thinking about my themes and process has given me a certain clarity of purpose. It’s allowed me to be clearer about what I’m interested in and what I want to explore in my writing.

I’ve been doing some research work for some academics at the OU about the climate crisis and creativity and that’s got me thinking about how I might combine my interest in home with my concern about the climate crisis. I guess I think of myself as both a writer and a researcher now, and that feels exciting and full of possibility.

I wish you all the very best with your PhD. It sounds fabulous, and important, and I am sure it will be an adventure worth having!

Rebekah Lattin-Rawstrone is the author of short story collection Glitches (Acorn Publishing, 2014) and novel Home (Red Button, 2015, now Kindle Direct Publishing). The working title of her PhD is Longing to Belong: an investigation into the potential for alternative storytelling techniques, in particular from the Middle East, to challenge narrative imperialism in the contemporary British novel.

Twitter: @RebekahLattinR; Website: www.lattin-rawstrone.com

Sarah Butler is the author of novels Ten Things I’ve Learnt About Love (Picador, 2013), Before The Fire (Picador, 2015) and Jack and Bet (Picador, 2020). The title of her PhD is Writing Home: an exploration of the writing of Jack and Bet (a novel) and a consideration of what the novel – as a space and a practice – offers to our understanding of the concept of home, and what a consideration of home offers to our understanding of the novel.

Twitter @SarahButler100; Insta: sarahbutlerwriter; Website: http://www.sarahbutler.org.uk/