Alistair Daniel, Associate Lecturer, Creative Writing

In June 1885, three Frenchmen – the prince Edmond de Polignac, Count Robert de Montesquiou-Fezensac, and the ‘celebrity gynaecologist’ Dr Samuel Jean Pozzi – arrived in London. They went shopping, had dinner with Henry James, and went home. It’s a thin premise for a story, fictional or real, yet from it Julian Barnes has woven a typically rich and absorbing tapestry in The Man in the Red Coat (2019).

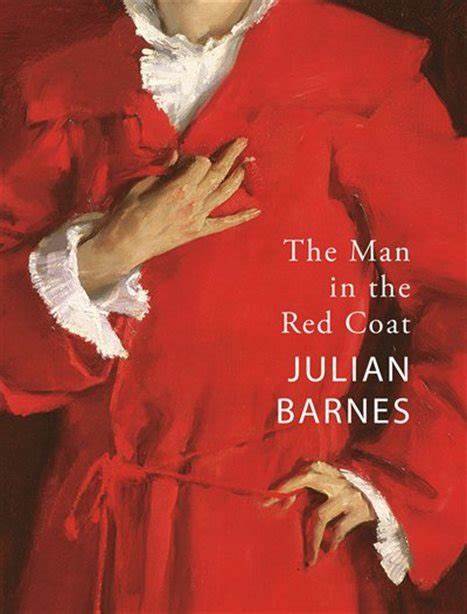

From A History of the World in 10 ½ Chapters (1989) to Levels of Life (2013), Barnes has spent a long and garlanded career eluding categorisation and The Man in the Red Coat is no exception. Is it a group biography, a biography, or something else? As a portrait of its three protagonists it’s more than lopsided, since Barnes largely ignores Polignac in favour of Montesquiou and Pozzi, both of whom make fascinating subjects in their own right. Montesquiou was a snob with a taste for cruelty, picking up talented boyfriends and destroying them when he grew bored. The dark allure of his character was not lost on artists of the time, and the count appears in several novels, including Huysmans’ À rebours (1884) and Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu (1913-27). He was also the model for Whistler’s Arrangement in Gold and Black (1891-2). It’s perhaps this artistic over-representation that encourages Barnes to focus on Pozzi, himself the subject of Sargent’s Dr Pozzi at Home (1881), a portrait that provides the cover, the title and the inspiration for this book.

If Barnes recounts Montesquiou’s bad behaviour with relish, his sympathies lie firmly with Pozzi, a pioneering surgeon whose innovations in hygiene and surgical technique radically improved survival rates, particularly for bullet wounds to the gut. He treated both public and private patients and was tireless in his promotion of high medical standards all over the world. He was also something of an international playboy, hobnobbing with celebrities and taking mistresses to Bayreuth. Nor did his professionalism prevent him from seducing his patients, and Barnes is careful to trace the impact of his behaviour on his long-suffering family through the journals of his outraged daughter Catherine.

Pozzi himself kept no journal, and it’s perhaps for this reason that The Man in the Red Coat sidesteps conventional biography. In fact, for long stretches the book neglects Pozzi in favour of a stroll through fin de siècle Paris, with Barnes as flâneur and guide. It’s a world populated by artists, including Oscar Wilde, Sarah Bernhardt, the Goncourt brothers, Huysmans, Proust and a host of less illustrious figures, like the Symbolist poet and novelist Jean Lorrain, who wasted his talent in endless feuds (he once fought a duel with Proust).

Writing in the fragmentary, episodic style familiar from his recent fiction (The Sense of an Ending, The Noise of Time), Barnes grants himself licence to stray into any area that takes his fancy – the Dreyfus affair, duelling culture, Oscar Wilde’s tour of the US – and in many ways The Man in the Red Coat reads as a compendium of familiar Barnesian enthusiasms, including Flaubert, literary style, the nature of biography and 19th-century France. As a result the book, while never less than entertaining, is more extended essay than biography, a companion piece to Something to Declare (2002), his essay collection on French culture, liberally sprinkled with colour plates and photo cards of fin de siècle celebrities. It meanders, with frequent detours, through Pozzi’s life in loose chronology, before eventually arriving at his demise.

One of Barnes’ preoccupations – here as elsewhere – is with the challenges of historical memory. ‘“We cannot know”’, he writes, ‘is one of the strongest phrases in the biographer’s language,’ and in a late section entitled ‘Things we cannot know’, Barnes lists some of the unanswerable questions that surround Pozzi’s life. Many novelists would view the gaps in the historical record as an opportunity, as Barnes is well aware: ‘All these matters could,’ he notes, ‘be solved in a novel.’ Which begs the question: why didn’t he weave a novel out of such rich – and tantalisingly incomplete – material? After all, he has done it before: both Flaubert’s Parrot (1984) and Arthur and George (2005) made fiction from nineteenth-century lives. It’s a question that only intensifies at the book’s denouement, when a disgruntled patient shoots Pozzi in the gut and the most celebrated surgeon of the age suddenly finds himself under the knife. Here Pozzi’s life assumes the pattern of art. For some novelists the symmetry would be irresistible (Ian McEwan made a similarly ironic plot twist the climax of Saturday). But Barnes is unmoved. As a novelist he is allergic to neat plotting and glib denouements and, as Sebastian Groes and Peter Childs have pointed out, ‘the unanswered and unresolved meanings of life and death suffuse all Barnes’s work’ (2011, p. 9). In Barnes’ view, it is not the job of fiction to stitch life into pleasing patterns and shapes. It’s only in non-fiction that ‘we have to allow things to happen – because they did – which are glib and implausible and moralistic’ (Barnes, 2019, p. 258). It’s this commitment to life’s complexity, and the limits of knowledge, that accounts for the book’s episodic structure, a structure that, through its gaps and silences, its detours and shifts in focus and tone, embraces mystery, leaves loose ends untied and offers more questions than answers. In Flaubert’s Parrot, Geoffrey Braithwaite likens biography to a fishing net, ‘a collection of holes tied together’ (Barnes, 1984, p. 38). Nearly 40 years on from that award-winning novel Barnes is still fishing in these philosophical waters, hauling lost treasures from the deep, inspecting the flotsam, and contemplating all the things lost at sea.

The Man in the Red Coat is available in hardback.

Barnes, J. (1984), Flaubert’s Parrot, London: Picador

Groes, S. & Childs, P. eds (2011), Julian Barnes: Contemporary Critical Perspectives, London: Continuum