In a new publication, OU Creative Writing lecturer Dónall Mac Cathmhaoill and Kevin De Ornellas of Ulster University explore ageism as presented in Edward Bond’s ‘Shakespearean’ trilogy about aged men

Negotiating Age: Aging and Ageism in Contemporary Literature and Theatre, edited by Mária Kurdi, and published by Debrecen University Press

It is argued that three plays by Edward Bond, born in 1934, should be regarded as a loose trilogy—and that the plays are united because they use the legacy of Shakespeare to provoke uncomfortable reflections on aging and ageism.

Two Bond plays are renowned for addressing the vexed legacy of Shakespeare head-on.

Lear (1971) is an uncompromising appropriation of King Lear in which Bond ‘corrects’ Shakespeare’s too-casual treatment of the under-represented effects of the mad king’s actions on the poor of the mismanaged kingdom of Britain.

Bingo (1973) is a bitter depiction of a dying Shakespeare who realizes that his art has been worthless because it has done nothing to frustrate murderous inequalities in post-Tudor England.

It is less well known that The Worlds (1979) is also a Shakespearean adaptation. The story of an arrogant company director, Trench, who loses his position and degenerates into a rabid, destructive, tramp-like, terrorist-supporting misanthrope, is an adaptation of Timon of Athens.

Bingo is a quasi-biographical conceit; the other two plays are radical appropriations.

Julie Sanders’s definition of appropriation as opposed to mere adaptation is important here. She argues that appropriation represents more decisive journey away from the informing text into a wholly new cultural product.

In other words, appropriations, such as those by Bond, are new works in their own right. They are not adaptations of Shakespeare but radical new plays contrived to perpetuate Bond’s theatrical, political, and moral vision.

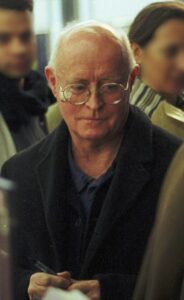

Edward Bond at the Théâtre National de la Colline, Paris, January 2001. Author: D. Tuaillon. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License.

Many critics have written about Bond’s engagement with Shakespeare—especially Lear and Bingo. But none have afforded The Worlds the same attention as the previous two.

Crucially, critics have, understandably, concentrated on the quasi-Brechtian staging techniques in Bond’s plays as well as the blistering, uncompromisingly leftist critiques of historical and contemporary economic and social inequalities. But none have addressed the arguably more humanistic issue of ageism.

This is important because the lead characters in the three plays are all victims of ferocious ageism. Despite his callousness, Bond’s Lear is a man more sinned against than sinning because his aged impotence and alleged senescence are met with even more overt contempt than in Shakespeare’s original.

Shakespeare, in Bingo, is openly mocked for willful inactivity by his supposed friend, Ben Jonson, and by his shrewish daughter, Judith.

And Trench, in The Worlds, is revered when fit to run his company but ruthlessly marginalized and discarded when he is forcibly retired from his own executive board.

The descent into psychological torment that all three lead characters endure is directly related to ageism. Aging is almost entirely presented as a cause for scorn and derision in these plays. Bond generally sidesteps any sense of aging well: in his plays, good aging cannot be bought. The three leading characters addressed in this essay do improve as people—but only within themselves and in a manner unnoticed and/or unappreciated by their contemporaries.

The plays are set variously in ancient Britain, in Jacobean England and in late-1970s Britain: it is widely acknowledged that Bond rightly or wrongly sees consistent economic discrimination across these vastly different eras. It should, we argue, also be apparent that Bond sees bigotry towards the aged as being another social malady that is consistent across centuries and even millennia.

Shakespeare’s plays are full of reflection on aging and on inter-generational conflict. Characters in Shakespeare plays often ‘retire’: King Lear relinquishes his kingship; Lady Macbeth skulks off and gives up on public life; and Prospero breaks his staff.

Across Bond’s three plays, he appropriates Shakespearean meditations on aging and juxtaposes them with his own observations about society’s disregard for those who are no longer economically productive.

This blog post is an adapted extract from: Kevin De Ornellas and Dónall Mac Cathmhaoill (2024) “You’ll Get Old Sitting There”: Contempt for Aged Males in Three ‘Shakespearean’ Works by Edward Bond. In: Kurdi, M. (ed.) Negotiating Age: Aging and Ageism in Contemporary Literature and Theatre. Debrecen University Press, 26-47.

The authors would like to thank Anoush Simon for practical assistance in the production of this essay.

Dónall Mac Cathmhaoill is a lecturer in Creative Writing at The Open University, United Kingdom. His research interests are in authorship and structures of production in theatre for social change, and theatre in post-conflict societies. Upcoming publications include a chapter on ethics and aesthetics in applied theatre in the Wiley Blackwell Handbook of Literary Evaluation, chapters on writing drama in the upcoming Creative Writing Handbook from Bloomsbury, and a monograph on post-conflict Irish theatre for University of Exeter Press.

Kevin De Ornellas is a Lecturer in English at Ulster University. His PhD is in English Renaissance Literature from Queen’s University Belfast, and his research focuses on drama on stage and on the page – especially Renaissance and post-War drama. He is also interested in the study of representations of animals and the environment in literature and culture. His publications include The Horse in Early Modern English Culture (2013), chapters in several books, among them The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Contemporary British and Irish Literature, and the Companion to Literary Biography. He is an editor of the forthcoming Wiley Blackwell Handbook of Literary Evaluation.