By Helen Owton

Women’s sport tends to receive less coverage in the media than men’s sport making female sports role models less available to young people, particularly in sports that are more traditionally male dominated such as football and rugby. During the sensational Six Nations 2016, we have seen another example of unequal exposure of sport. Whilst women’s football seems to be increasing their exposure, women’s rugby still have even further to go.

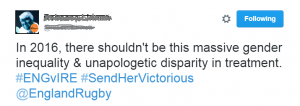

On Saturday 27 February 2016, the TV coverage and social media was trending with #EngvIre #RBS6Nations tweets about the Six Nations game; this was the men’s rugby. Afterwards, England Rugby sent out the following tweet:

And requested changing the hashtag to #SendHerVictorious.

England women maintained their unbeaten record by defeating Ireland (13-9). Despite their win, the next two rounds might prove tough for England; will they have the skill, speed, strength and tactics to beat Wales on 12 March 2016 at Twickenham and then France (away) on 18 March 2016? On Sunday 28 February, Wales beat France 10-8 and Italy took their first victory by beating Scotland 22-7 [full fixture list here].

Yet all these sensational women’s Six Nations games had no TV coverage and the fans were left hunting the internet for a link on England Rugby which streamed the England match live. The audience at home were not happy; people all over the world were complaining about the lack of live TV coverage, online streaming problems and the clear disparity of the women’s exposure compared to the men’s.

Whilst the Six Nations website shows the current up-to-date standings for the men’s Six Nations, there is not one for the women’s Six Nations event. The newspaper coverage before and after the Six Nations women’s rugby games was equally poor. In 2016, this disparity simply does not make sense.

Risk and rugby

When Sarah Chester suffered a fatal injury in 2015 after being tackled in a rugby game evoked arguments of whether women should even be playing rugby despite men’s fatal injuries from rugby as well. We’ve seen similar fears in women’s boxing which is a moral (women who box risk fatal injury) in the well-known film Million Dollar Baby. Some might argue that these are fear tactics aimed at putting women off traditionally male-only sports. However, the inclusion of women’s boxing at the 2012 London Olympics and the 2015 European Games at Baku has been a sign of progress.

Women’s sports media exposure

Since 2012, the talk appears to have been about what legacy was left for women’s sports but there is a very long way to go before there is gender equality in all sports. Despite the growing awareness of gender inequality in sport, it is well documented that women’s sport remains second to men’s sport in many ways (e.g. media coverage, wages, prize money, sponsorship and status), which has wider implications for equality in sport, and in society. Cooky, Messner and Hextrum (2013) reported that televised coverage of women’s sports was at its lowest yet at 1.6%. Whilst coverage increases slightly for major events (e.g. Wimbledon, Olympics), the type of coverage has been subjected to critical analysis. The report ‘Women In Sport’ (2015, p. 3) produced the following figures on women’s media coverage:

- Women’s Sport makes up 7% of all sports media coverage in the UK

- Just over 10% of televised sports coverage is dedicated to women’s sport

- 2% of national newspaper sports coverage is dedicated to women’s sport

- 5% of radio sports coverage is dedicated to women’s sport

- 4% of online sports coverage is dedicated to women’s sport

Additionally, they found that women’s sport received 0.4% of reported UK sponsorship deals in sport between 2011-2013. This sponsorship gives further greater exposure to men’s sport. Fink (2014) argues that “female athletes and women’s sport still receive starkly disparate treatment by the sport media commercial complex compared to male athletes and men’s sport” (p. 331). It’s 2016 and the way women’s rugby was reported demonstrated how rugby is still rated as second-class to the men’s. This then feeds messages that rugby (and other sports) participation is more appropriate for boys and men than for girls and women; that women are naturally inferior to men, and that women’s sport is less important than men’s sport. A lack of exposure to skilful sportswomen from a broad range of sports in the media could be a reason why the use of derogatory ‘like a girl’ comments perpetuates.

Whilst an argument could be made that there isn’t enough money generated in the women’s game to pay women higher salaries, improving the media coverage to the 9.63 million viewers who watch men’s rugby might generate the interest in women’s rugby thus improving their wages and the value of women’s sport. However, arguing for media coverage to be increased is difficult in light of the seemingly lack of value placed on women’s sport. If a report in 2015 on business leadership roles estimates that without any more efforts to promote women’s equality in management, it will take 100 to 200 years to achieve gender parity, then how long will it take to achieve gender parity in all sports? Given the statistics and the missed opportunity for the British press to report a double win in the women’s and men’s rugby Six Nations this week, the future looks long and winding.

The rugby world does seem to be making an effort to challenge stereotypes (e.g. Link to advert) and raise exposure (#SendHerVictorious) and respect to the women’s game but it’s about time the public and the media gave the women’s rugby the conversion they deserve!

- Gender in sport is explored in our new module E314.