By Helen Owton & Meg-John Barker (With expertise input from Joseph de Lappe)

The new Batman v Superman film, Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice, is coming out on 25th March 2016 so we thought this would be a good chance to reflect on superhero movies: particularly the place of gender in them.

We’re particularly interested in the role of binaries and hierarchies in these kinds of films. Batman v Superman pitches two well-known superheroes against each other in a binary way, and – of course – the superhero genre as a whole is based on the linked binaries of hero v villain, good v bad, and right v wrong, with the former winning out in the end. More recent versions of superhero movies trouble these simple distinctions somewhat. For example, The Dark Knight version of Batman is less clear cut, and the two groups of X-men can be seen as more about assimilationism v radical approaches to activism. However, audiences may well not pick up on such nuances.

An additional binary and hierarchical consideration in Superhero movies is needed. Characters are male or female, with predominantly male characters, and masculinity is privileged over femininity in various ways.

Currently, we are living through a golden age of comics, with a vibrant independent comic and graphic novel scene which includes strong representations of women and LGBT+

and LGBT+ characters, much of which has been taken up by mainstream superhero comics

characters, much of which has been taken up by mainstream superhero comics too. Nonetheless, there is a serious disparity between this shift in comics, and the continued limited representation in the movies which are based on these comics.

too. Nonetheless, there is a serious disparity between this shift in comics, and the continued limited representation in the movies which are based on these comics.

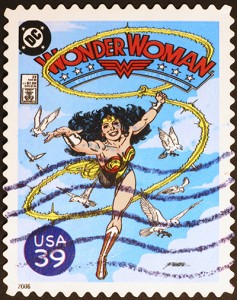

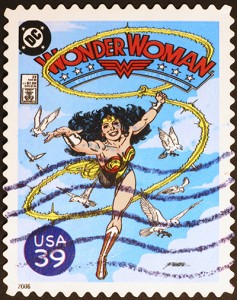

Wonder Woman and women/men in superhero movies

You might be surprised to learn that Wonder Woman is making an appearance in Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice given that both title and trailer suggest that the film will revolve around two well-known male superheroes. In superhero comics Wonder Woman has been part of the recent positive trend towards strong representations of women, notably with Gail Simone ’s seminal run writing for Wonder Woman. However, turning to the movie, Wonder Woman actor Gal Gadot (who served two years as a sports trainer in the Israeli Defense Forces) has been blasted on social media already for being too slim, not busty, and not fit enough to play the part, but this should not be surprising given that women tend to be more heavily criticised on appearances. Not only is there a complete lack of women in superhero films, but the women are either cast as damsels in distress

’s seminal run writing for Wonder Woman. However, turning to the movie, Wonder Woman actor Gal Gadot (who served two years as a sports trainer in the Israeli Defense Forces) has been blasted on social media already for being too slim, not busty, and not fit enough to play the part, but this should not be surprising given that women tend to be more heavily criticised on appearances. Not only is there a complete lack of women in superhero films, but the women are either cast as damsels in distress (e.g. Lois Lane) which serves to infantilise women, or as sidekicks to a main male character(s). This is the case in many of the recent X-men and Avengers movies, for example, very few of which pass the Bechdel test

(e.g. Lois Lane) which serves to infantilise women, or as sidekicks to a main male character(s). This is the case in many of the recent X-men and Avengers movies, for example, very few of which pass the Bechdel test (a simple test with three criteria: 1) features two or more female characters, 2) who have a conversation with each other at some point, 3) about something other than males). It also seems a shame that the Bechdel test is still what we’re aiming at rather than, for example, equal numbers of male and female characters, and female characters playing a major role.

(a simple test with three criteria: 1) features two or more female characters, 2) who have a conversation with each other at some point, 3) about something other than males). It also seems a shame that the Bechdel test is still what we’re aiming at rather than, for example, equal numbers of male and female characters, and female characters playing a major role.

(Illustration: ‘Wonder Women’ by Helen Owton, 2016, Pencil, 297x420mm, 130 gsm white cartridge paper)

Hopefully, the inclusion of Wonder Woman in Batman v Superman is a precursor for the specific Wonder Woman movie due for release in 2017. However, we fear in the Batman v Superman movie that she will end up merely a sidekick behind the two white heterosexual hyper-masculinised superheroes, thus positioning her as second-class to the men.

movie due for release in 2017. However, we fear in the Batman v Superman movie that she will end up merely a sidekick behind the two white heterosexual hyper-masculinised superheroes, thus positioning her as second-class to the men.

It is worrying that Batman v Superman continues with the same hyper-masculine aesthetic that has defined superhero movies for so long. For example, superheroism enables individuals to express aggression, competitiveness, speed, strength, invincibility, and skill – traits commonly associated with hegemonic masculinity. Hegemonic masculinity is white, heterosexual, privileged/middle-class, and able-bodied masculinity which is generally represented as opposite and superior to femininity and homosexuality (Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005). Thus hegemonic hyper-masculinity marginalises other masculinities (e.g. black, disabled, working class, gay) and devalues femininity (Connell, 1987). Also, the hyper-masculinity expressed in superhero movies is frequently tortured, addicted, lonely, and painful. We could reflect on the gendered violence inherent in the messages this gives to young male viewers about (hyper)masculinity requiring such suffering.

Unlike Wonder Woman there are many female superheroes that have not made it into films as sidekicks let alone solo or lead roles in a film (e.g. Ironwoman, Batwoman, Spiderwoman, Ms Marvel, She-Hulk). When women superheroes do appear, often they are dressed in over-sexualised costumes in an attempt to appeal to a presumed male heterosexual audience. They are scantily clad (e.g. Elektra) or dressed in PVC (e.g. Catwoman). Attempts to gender-flip the outfits and postures

in an attempt to appeal to a presumed male heterosexual audience. They are scantily clad (e.g. Elektra) or dressed in PVC (e.g. Catwoman). Attempts to gender-flip the outfits and postures of superheroes have usefully drawn attention to how sexualised and ridiculous female superhero costumes and postures often are. These attempts also draw attention to the clear male/female binary that is in play (when women are represented at all in superhero movies). It is possible to gender flip characters – and find the results ridiculous – because the depictions are so very binary: hypermasculine male characters and hypersexualised female characters.

of superheroes have usefully drawn attention to how sexualised and ridiculous female superhero costumes and postures often are. These attempts also draw attention to the clear male/female binary that is in play (when women are represented at all in superhero movies). It is possible to gender flip characters – and find the results ridiculous – because the depictions are so very binary: hypermasculine male characters and hypersexualised female characters.

Battling the super-binary

Just as superhero films rarely radically challenge binary ways of thinking about moral values (e.g. good v bad, wrong v right), also they rarely question gender binaries (men v women, masculine v feminine), or the related ways in which men have been privileged in terms of legal status, formal authority, political and economic power, access to resource, and sexuality. They do little to challenge a gender ideology that is based on a simple binary classification model which comes with quite fixed ideas about how to understand sex and gender. This binary model suggests that all people can be classified into one of two sex categories: male or female. These sex categories are identified as oppositional and defined in biological terms. According to the model, males are assumed to be completely different (in terms of feelings, thoughts and actions) from females which then form the expectations for the ways people define and identify gender (masculine and femininity). This gender ideology is so deeply rooted in our social worlds that we hardly think to question this organising principle (Coakley & Pike, 2009). This means that many people resist thinking about gender in new ways and often feel uncomfortable when others do not fit neatly into one sex category or the other; a problem experienced by many trans athletes competing in sport. This classification of all bodies into two separate categories appears to reflect social and cultural ideas rather than biological facts (Jordan-Young, 2010). Evidence suggests that sex/gender isn’t entirely binary on any level of physiology or psychology (chromosomes, hormones, brain structure, personality, gender roles, Fausto-Sterling, 2000). For example, Daphna Joel ’s research (2011, 2015) has found that it is extremely rare for anybody to have what used to be thoughts of as a ‘male’ or ‘female’ brain: most people’s brains display a mixture of features

’s research (2011, 2015) has found that it is extremely rare for anybody to have what used to be thoughts of as a ‘male’ or ‘female’ brain: most people’s brains display a mixture of features . And on the level of experience, over a third of people

. And on the level of experience, over a third of people said that they were to some extent the ‘other’ gender, ‘both genders’ and/or ‘neither gender’.

said that they were to some extent the ‘other’ gender, ‘both genders’ and/or ‘neither gender’.

Superqueering gender

If we are to shift the hierarchical positioning of men as superior to women in the superhero movie genre (and beyond), perhaps we need to go further than fighting for the inclusion of equal numbers of female characters at an equal level to male characters, and no more sexualised than male characters. Perhaps we need to also encourage the inclusion of characters who question the assumption of a fixed gender binary. One way of shifting the notion of fixed binary genders is to challenge the expectation that conventionally ‘male’ characters need to remain male in the movie versions, and to be played by male actors. Given the historical context of most of the superhero comics things are unlikely to change until some of the sidekick/damsel in distress female characters are elevated to heroes in their own right and writers and directors recognise that just because a character was originally depicted as a straight, white, male, doesn’t mean they have to remain that way. There are several examples of such shifts in superhero comics , although these are often received with at least as much criticism as celebration from readers. Another, more radical option, is the inclusion of more characters who explicitly challenge the gender binary, either by focusing on already non-binary characters, or by making currently binary characters non-binary. There are a few possibilities already available in the superhero canon. For example, the character of Loki

, although these are often received with at least as much criticism as celebration from readers. Another, more radical option, is the inclusion of more characters who explicitly challenge the gender binary, either by focusing on already non-binary characters, or by making currently binary characters non-binary. There are a few possibilities already available in the superhero canon. For example, the character of Loki in the Thor/Avengers comics and movies who can shapeshift different genders. Although Neil Gaiman’s Sandman series (not a conventional superhero series) has come up against glitches

in the Thor/Avengers comics and movies who can shapeshift different genders. Although Neil Gaiman’s Sandman series (not a conventional superhero series) has come up against glitches in attempts to be developed into a movie, it also includes an androgynous character, Desire

in attempts to be developed into a movie, it also includes an androgynous character, Desire , who appears in different genders (as do other characters at times). However it’s worth noting that both these characters are probably closer to being villains than heroes, reflecting the way in which non-binary characters – like bisexual characters – tend to be represented as evil, manipulative, and suspicious. Also already non-binary characters do not have to be the limit. Just as there seems to be no reason not to have a female actor playing Hulk or Professor X, is there any reason not to have a non-binary Spider or Bat person? There are already a number of far more explicitly queer/trans superhero comics which could be adapted for the screen, such as The Young Avengers

, who appears in different genders (as do other characters at times). However it’s worth noting that both these characters are probably closer to being villains than heroes, reflecting the way in which non-binary characters – like bisexual characters – tend to be represented as evil, manipulative, and suspicious. Also already non-binary characters do not have to be the limit. Just as there seems to be no reason not to have a female actor playing Hulk or Professor X, is there any reason not to have a non-binary Spider or Bat person? There are already a number of far more explicitly queer/trans superhero comics which could be adapted for the screen, such as The Young Avengers ,the wicked + the divine

,the wicked + the divine , Astro City #16

, Astro City #16 , or Grant Morrison’s and Rachel Pollock’s runs on Doom Patrol

, or Grant Morrison’s and Rachel Pollock’s runs on Doom Patrol , if film-makers could get past always returning to the same set of heroes and villains. Queering superhero movies in this way not only has the potential to empower queer and trans audiences through seeing themselves represented, but also it can liberate straight and cisgender audiences by offering something other than rigid binaries of hypermasculinity and sexualised femininity.

, if film-makers could get past always returning to the same set of heroes and villains. Queering superhero movies in this way not only has the potential to empower queer and trans audiences through seeing themselves represented, but also it can liberate straight and cisgender audiences by offering something other than rigid binaries of hypermasculinity and sexualised femininity.

Conclusions

As with other intersecting identities such as disability, race, class, and sexuality, clearly there is still a very long way to go with gender in the superhero movie genre. Whilst the inclusion of Wonder Woman in Batman v Superman could be seen as a step forward, it still feels like a small step indeed, and it remains to be seen whether the movie even passes the low bar of the Bechdel Test. In future media representations it would be great to see female characters on an equal footing with male characters, women actors playing originally male characters, films with central female superheroes (like the Netflix series, Jessica Jones ), and all-female cast superhero movies (as with the new Ghostbusters

), and all-female cast superhero movies (as with the new Ghostbusters film), explicit gay/lesbian characters (like Xena: Warrior Princess

film), explicit gay/lesbian characters (like Xena: Warrior Princess ), men playing more feminine characters and women more masculine ones, and explicitly trans and non-binary characters and actors in both leading and supporting roles.

), men playing more feminine characters and women more masculine ones, and explicitly trans and non-binary characters and actors in both leading and supporting roles.

This entry was posted on OpenLearn. Read the original article.

“I wasn’t very good at school and to be honest I didn’t really enjoy it. I just wasn’t really interested. I got some GCSEs, though at D and below and I felt I had the ability but I just didn’t work hard. The Open University gave me another chance – to do what I really wanted to do, study sport and fitness and have a career after the army.

“I wasn’t very good at school and to be honest I didn’t really enjoy it. I just wasn’t really interested. I got some GCSEs, though at D and below and I felt I had the ability but I just didn’t work hard. The Open University gave me another chance – to do what I really wanted to do, study sport and fitness and have a career after the army. The flexibility of the OU suited the way I wanted to learn, away from a classroom and in my own time. The course also gave me a grounding in all the relevant subjects and the quality of the learning materials was good and well produced. The tutors were all contactable and highly knowledgeable in their subject and did their best to answer any questions.

The flexibility of the OU suited the way I wanted to learn, away from a classroom and in my own time. The course also gave me a grounding in all the relevant subjects and the quality of the learning materials was good and well produced. The tutors were all contactable and highly knowledgeable in their subject and did their best to answer any questions.